Ezra Pound and TS Eliot in Excideuil

A slightly shorter version of this article was originally published in Make It New - the online journal of the Ezra Pound Society - in December 2017. I am grateful to Roxana Preda, editor of Make It New, for her encouragement in writing this article.

Copyright © 2017 J.G. McKechnie

The Castle of Excideuil

Recollections? let some

thesis-writer have the satisfaction of “discovering” whether it was 1920 or ’21 that I went from Excideuil to

meet a rucksacked Eliot. Days of

walking—conversation? literary? le papier Fayard[1]

was then the burning topic. Who is there

now to share a joke with? Am I to write “about” the poet Thomas Stearns Eliot? my friend “the Possum”? Let

him rest in peace. I can only

repeat, but with the urgency of fifty years ago: READ HIM.

Eliot and Pound shared many experiences over a fifty-year

period. So why was it to Excideuil that Ezra Pound referred in his brief

recollections?

Excideuil is an unpretentious small town in the Périgord, in

south-western France France

Excideuil lies in the heartlands of the medieval troubadours.

Giraut de Borneil came from Excideuil, and the town's lycée today bears his name. Arnaud Daniel was from Ribérac, in the

western Périgord, about 60 kilometres from Excideuil. Bertrand de Born was lord

of Hautefort, 10 kilometres southeast of Excideuil. Both he and Bernard de

Ventadour died at the Cistercian monastery of Le Dalon, 12 kilometres east of

Excideuil. Richard Coeur de Lion, some of whose troubadour verses survive and

who unsuccessfully besieged Excideuil in 1182, was killed at Châlus, 35

kilometres to the north, in 1199.

Châlus

View of the historic rock where Richard Coeur

de Lion was wounded in 1198 (PFP 220)[2]

While these twelfth-century ghosts and associations no doubt

resonated with the two visiting poets, there must have been more to their days

together in Excideuil for Pound to have singled them out in his elegy.

*

Ezra Weston Loomis

Pound was born on 30 October 1885 in Hailey ,

Idaho St Louis , Missouri London Germany England England

Ezra Pound married

Dorothy Shakespear, a painter, in 1914. TS Eliot married Vivienne (later

Vivien) Haigh-Wood in 1915. Dorothy, but not Vivien, was in Excideuil in August

1919, and her postcards provide us with much of the detail of that time. Some

were sent in 1919; she kept others as souvenirs and annotated them in green ink

many years later, probably around 1970. Ernest Hemingway thought Dorothy

"very beautiful and wonderfully built," and wrote "Dorothy's

paintings I like very much" (Hemingway, 87). On the other hand, WB Yeats,

who had had an affair with her mother, described Dorothy's drawings as

"the most monstrous cubist pictures" (Moody 2007, 252). Vivien stayed

behind in England when her

husband went to France

The cover of Pound's Ripostes was designed by Dorothy.

The two poets had met

in London

Then in 1914... my meeting with

Ezra Pound changed my life. He was enthusiastic about my poems, and gave me

such praise and encouragement as I had long ceased to hope for. I was happier

in England , even in wartime,

than I had been in America

In 1918, Eliot

wrote of Pound that "I value his verse far higher than that of any living

poet" (LTSE1, 254). In 1935 he wrote that Pound "is more responsible

for the twentieth-century revolution in poetry than is any other

individual" (LE, xi). Pound's persistence was critical to the 1915

publication of The Love Song of J. Alfred

Prufrock, Eliot's breakthrough poem.

Pound was deeply

affected by the War, devastated by the loss of friends, distressed by work that

he felt kept him from writing poetry, disillusioned with Britain France

Ezra and Dorothy

set off for Toulouse Toulouse Toulouse

Postcard

Ezra Pound sent to his mother-in-law from Toulouse

on 24

April 1919

I have lain in Rocafixada,

level

with the sunset,

Have seen the copper come down

tingeing

the mountains,

I have seen the fields, pale, clear

as an emerald,

Sharp peaks, high spurs, distant

castles.

I have said: "The old roads

have lain here.

Men have gone by such and such

valleys

Where the great halls were closer

together."

I have seen Foix on its

rock, seen Toulouse

Ezra sent a

postcard from Foix on 22 June 1919 and he and Dorothy walked into Foix again a

few days late to find flags flying in celebration of the Peace[3]

that had just been signed. The immediate aftermath of Great War was very much

present in the summer of 1919.

1919

sketch of the Pyrenees by Dorothy Shakespear[4]

The coming visit

to Excideuil was, however, clearly planned and present in Pound's mind during

those months based in Toulouse Toulouse Paris Sept, London Toulouse

Early on the

morning of 24 July, Ezra and Dorothy left Toulouse

Postcard Dorothy sent from Brive on 24 July 1919

On 25 July,

Dorothy sent a postcard from Excideuil giving a forwarding address there (PFP

pc not numbered) -

Please forward letters

to us at

Hotel Poujol

Excideuil

"until further orders". It

is a small village with lovely ruins - of towers & a château, & this entrance gate. I will write

in a day or so. Love D.

Postcard showing the entrance gate to the Castle of Excideuil

*

Ezra Pound had been to Excideuil before - briefly in early

June 1912 (WTSF, 24). His poem Provincia

Deserta, based on his 1912 travels, mentions the town of Excideuil

I have gone in Ribeyrac

and

in Sarlat,

I have

climbed rickety stairs, heard talk of Croy,

Walked over

En Bertan's old layout,

Have seen Narbonne

Have seen

Excideuil, carefully fashioned.

I have

said:

"Here

such a one walked.

"Here

Coeur-de-Lion was slain.

"Here

was good singing.

"Here

one man hastened his step.

"Here

one lay panting."

I have

looked south from Hautefort,

thinking

of Montaignac, southward.

He obviously liked "Excideuil, carefully

fashioned". His 1912 notes describe it thus (WTSF, 26) -

A couple of great fields

set up along with the church

spire, the sky pale blue

& white after the sunset,

with the tree on the skyline

outlined against it,

& the great gentle tower

clear edged,

unascendable, and

for no known reason

these things wrought

out a sort of perfect mood

in things,

the air was after rain

damp & coolish.

From all the places he had been on the first leg of his 1912

quest for towers and troubadours, it was in Excideuil that he chose to base

himself in the summer of 1919.

Excideuil was then, as now, a relatively out-of-the way

place. It merited only two lines in Baedeker[5] -

The chief station on this interesting

route is Excideuil, with a château of

the Talleyrand-Périgord family (13-16th cent.).

Smith's Troubadours at

Home, which Pound had consulted, was somewhat more expansive -

In the midst of this region we

come upon the pleasant little village

of Excideuil

Smith saw the castle at Excideuil as "a stern,

uncompromising, unrelenting fragment of the Middle Ages" (Smith, 259).

Dating in parts to the work of the Viscounts of Limoges in the 11th century, it

had replaced an earlier fortress in wood that had proved inadequate against

Viking raids (Thibaud, 60).

The Talleyrands acquired the castle of Excideuil through

marriage early in the 17th century, and in 1613 added the title Marquis of

Excideuil to their many other titles. They only began to use the style

"Talleyrand-Périgord" in about 1750, in order to emphasise their

descent from the medieval - "Tallairan" or "Tairiran" - Counts

of the Périgord.[6] In

addition to holding the title of the Marquis of Excideuil, the Talleyrands were

also the Princes of Chalais. From the time of their ownership of Excideuil, the

castle there and the town itself began to decline in favour of other preferred

residences such as that at Chalais. The Talleyrands disposed of Excideuil in

1883. While Ezra Pound certainly visited Chalais on his 1912 walking tour, I do

not think that he and Dorothy visited it again in 1919 on an excursion from

Excideuil. On the back of a postcard of Chalais in the Pound Family Postcard

Collection (PFP 213) Dorothy wrote (1970?) "Dalleyrand Berigord".

This echoes Pound's Canto CV which begins

Feb.1956

Is this a divagation:

Talleyrand

saved Europe for a century

and in which later

lines read

33 years after the Bard's death...

"Dalleyrand"

800 years after En Bertrans

"en gatje",

had the four towers,

"Dalleyrand

Berigorrr!" (CV/769)

Dorothy's 1970 note does not necessarily suggest that they

visited Chalais together in 1919.

Ezra and Dorothy did, however, take other excursions from

Excideuil in the summer of 1919, many miles of them of them on foot - as Pound

had mentioned they intended to do in his 21 July letter to his mother. As a

prelude to the walks best documented in the postcards, they probably took the

train from Excideuil to Hautefort on 1 August 1919. In the twelfth century Bertrand de Born was the lord of Hautefort.[7]

Travellers from Excideuil to Hautefort, now as

then, cross the valley of the Auvézère on their way. This country was visited

in more detail by Ezra Pound in 1912 and celebrated in exquisite lines in Near Perigord [8] -

Bewildering

spring, and by the AuvezerePoppies and day's-eyes in the green émail

Rose over us; and we knew all that stream,

And our two horses had traced out all the valleys;

Knew the low flooded lands squared out with poplars,

In the young days when the deep sky befriended.

And great wings beat above us in the twilight,

And the

great wheels in heaven

Bore us

together... surging... and apart...

Believing

that we should meet with lips and hands. (P,154)

T.E. Lawrence

(later "Lawrence of Arabia"), visited Hautefort on his 1908 cycling

tour of France

Hautefort in 1908, photographed by T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia )[9]

Here are some

of Pound's 1912 notes on Hautefort

(which he here calls by its Occitan name Altafort) (WTSF, 22) -

Altafort is, as I have said,

rebuilded, but it is set in a great nave of a hill, to match the brag of its Born, backed with pine wood steep,

breathlessly steep to the south and

lording it over two far stretches of valley, so that for long the fiery chatelain might have seen them burning

his trees, & trampling down his grain.

In Near Perigord, this became "...one

huge back half-covered up with pine".

Having seen

Hautefort in a state of partial ruin, Ezra Pound was interested to hear how it

had been under previous ownership from a man he met on the tram from Excideuil

to St Yriex (WTSF, 28) -

Awaiting the tram I fell in with a

comfortable man from Sarlat & he dealt likewise

in garments for the dead, from him I gathered the remaining history of Hautefort: that he remembered visiting it

20 yrs ago when it belonged to De Damas

percepteur to the king who might have been Henry V. At this time there always stood a guardsman in jack boots on

either side of the drawbridge &

seigneurial state pertained. The chateau was later sold at a bargain price to Armides [sic] who'd made his fortune in the Panama

In 1929, the

Château of Hautefort was rescued from abandonment by Baron Henry de Bastard and

his wife, Simone. The baron died in 1957, when the restoration was still

incomplete. Only by 1965, had enough been done for his widow to take up

residence in the castle. Then, in 1968, Hautefort was swept by a devastating

fire, news of which reached Dorothy Pound. On the back of a postcard of

Hautefort, Dorothy's green ink records "I am told this has been destroyed

(burnt down?)" (PFP 221).

Hautefort in 1919

Simone de Bastard

almost immediately set out on another round of restoration. The splendid

results are what we see today.

Hautefort, July 2012

In 1912, Pound had only, as in Provincia Deserta, "looked south from Hautefort, thinking of

Montaignac, southward." Here, Pound is thinking the thoughts of Bertrand

de Born, a theme picked up again in Near

Perigord -

En Bertrans, a tower-room at Hautefort

Sunset, the ribbon-like road lies, in red cross-light,

Southward toward Montaignac [...] (P,151-2)

One of the ladies of his poetic longings, Maent, was

châtelaine of Montignac,[10]

though, in Near Perigord, Pound

questioned the bellicose troubadour's motives -

He loved this lady in castle

Montaignac?

The castle flanked him - he had

need of it. (P,150)

In 1919, Ezra and Dorothy walked south from Hautefort to

Montignac. From Montignac, Dorothy sent a postcard of the Château of Hautefort on

2 August to her mother (PFP 3) -

We spent last night at Altaforte &

started out soon after 6 am. for here. Déj here & dinner and on a short way

by train. It was a lovely walk about 16 miles over highish hills. This is where

Bertrand de Born's "Maint" lived. Last night we slept close to where

Henry II's men probably camped besieging B. de Born.

Postcard of Hautefort sent from Montignac by Dorothy to her mother on

2 August 1919

On the back of a postcard of the ruins of the feudal castle

at Montignac, Dorothy's later note recalls (PFP 60) -

EP DP

rested here - dinner and train to

? "Les Prunes" - train about 1 1/2 late [sic], owing to picking - up

the harvest of les Prunes in crates along the line.[11]

Maent's Castle in Montignac in March 2018

They travelled on to Sarlat ("And Cairels was of

Sarlat" - VI/23) and from there walked to the Dordogne River Dordogne

near Souillac, we read (PFP 12) -

EP DP

from Sarlat - to ? & I

believe after miles of v. rough country walk that it was there that we saw the

grasshoppers with sunset wings--

Five years later, Ezra would recall the experience in the

last line of Canto XVII - "Sunset like the grasshopper flying".

Front and back of a postcard of the Dordogne near Souillac

with "grasshoppers with sunset

wings" mentioned on the back.

From the Dordogne valley they

went on to Rocamadour. Dorothy sent another postcard to her mother from

Rocamadour, the text spilling on to the front of the card (PFP 2534) -

Aug 5,1919

We came over the hills across

gorgeous bare scrub, stirring up 1000s of butterflies, from a town on the Dordogne . This is a place of pilgrimage, since all time -

and there are a black Virgin & a miraculous bell & 200 and something

steps up the village that they crawl up on their knees in Sept: full of

tourists devout & otherwise, but a really amazing place all tucked against

the huge rock. The Dordogne is gorgeous

scenery & a large river. We struck a dozen or so Russian soldiers signing

magnificently in a café on Sunday evening. train today to Brive. Have had three

long wonderful walks. D.[12]

Postcard of Rocamadour sent by Dorothy on 5

August 1919

On another postcard of Rocamadour, Dorothy's later notes tell

us (PFP 24) that "we ended a v: long tramp here - gave me 'the horrors' for fanaticism." In 1912, Pound

had omitted Rocamadour from his itinerary in order not to "begin a

digression on religion".

There are suggestions that Ezra and Dorothy visited Ventadour

and neighbouring Ussel in 1919.[13] While Ezra did visit these places in 1923,

with Olga Rudge (Conover, 7)[14],

I have been unable to locate evidence for a 1919 visit. The castle at Ventadour

has in recent years undergone some restoration, but it was as remote ruin that

Ezra would have seen it in 1923, as beautifully depicted in his Canto XXVII -

Where was

the wall of Eblis

At

Ventadour, there now are bees,

And in that court, wild grass for

their pleasure

That they carry back to the

crevice

Ventadour[15]

Ezra and Dorothy may also have visited Poitiers ,

once the seat of Guillaume IX of Aquitaine Poitiers Poitiers Poitiers

*

In April 1919, before he left London

Like Ezra Pound, TS Eliot had visited the Périgord before,

though probably not Excideuil itself. His first visit was in the winter of

1910-11 during "that magical year" (Miller, 115) that he spent as a

student in Paris (LTSE1, 20) -

At Christmas I travelled for two

weeks in France , and saw

several things not often visited - including Poitiers ,

Angoulême, Toulouse

We know that "other places" included Périgueux

(LTSE1, 403). Crawford (157) suggests that he may have travelled through the

south west of France

For Jean Verdenal, 1889-1915

mort aux Dardenelles

Hargrove (47) suggests that near Périgueux "...his

interest in primitive cultures perhaps led him to visit some of the caves, such

as the Grotte de Rouffignac with over 250 prehistoric drawings and the Abri du

Cap Blanc with its paintings of horses, bison and deer over 14,000 years

old." In "Tradition and the Individual Talent", published in the Egoist in September 1919, though

written before he left for France

in August 1919, Eliot mentions "Magdalenian draughtsmen" as a part of

"the mind of Europe ".[17]

No doubt he was anticipating a return visit, if he had indeed been there

before, to some of the Dordogne 's pre-historic

sites as part of his summer holiday. Its now most famous pre-historic site, Lascaux , near Montignac, had not yet been discovered in

1919. Font de Gaume was then the leading attraction featuring polychrome

paleolithic paintings.

Eliot left London London , he described his

journey across France , how

at Le Havre Trouville (it

was "a blazing bright August day") and from there the train to Paris Limoges

It began to be light, and I could

see the beautiful landscape of the Périgord, hilly and wooded, very different

from Northern France . You feel at once that

you are in a different country, more exciting, very southern, more like Italy village

of Excideuil

In a subsequent letter to his mother (14 October 1919), he

takes up the story of his summer holiday in France (LTSE1, 403) -

Périgueux is a town that I like.

The last time I was there was at Christmas (1910), and arriving early on an

intensely hot August morning it seemed more southern than it had before. It is

a small old town, the metropolis of that district. It had taken me thirty-six

hours to get there, but I felt I had left London

- the London France

and Italy

The 14 October letter breaks off with him sitting in the

garden and Eliot wrote no further to her, at least in letters that survive,

about the details of his 1919 holiday.

The station at Excideuil on the "Tramway". Eliot and Pound would have arrived here together in 1919, as Pound would have done in 1912.[19]

Eliot, who was working in a London bank then, was unwell when

he arrived in Excideuil. [20] He was

worn down by war-time London France

I am very tired (as you will have seen from this letter) and very glad

to be getting out of London

Ezra Pound wrote to that he hoped "to put him

[Eliot]through a course of sun, air & sulphur bath & return him to London

After a few days

in Excideuil, Eliot set off with Pound on 16 August and walked from Excideuil

to Thiviers, leaving Dorothy behind in Excideuil. The summer weather was hot -

"intensely hot" (Eliot), "very, very hot" (Dorothy).

Ezra sent a

postcard to Dorothy from Thiviers on the morning of 17 August (PFP 5) -

Thiviers reached without incident.

Mist this a.m. Chateau Feyloli no post card available. Love E. Sunday a.m.

The

postcard Ezra Pound sent from Thiviers on 17 August 1919 to his wife, Dorothy,

at the Hotel Poujol in Excideuil.

Thiviers sits on a

hilltop, astride the old Roman road from Limoges

a prettily

situated commercial town (pop.3284), with a Romanesque church of the 12th cent

and the fine renaissance Château de

Vococour (now a hotel).

Thiviers,

July 2011

The

château de Thiviers (or Vaucocour) is in the foreground with the church tower

rising behind

The enigmatic

reference to "Chateau Feyloli" in Ezra's 17 August postcard is a

reference to Château de la Filolie, just beyond the northern suburbs of

Thiviers. It was then owned by the millionaire fascist perfume manufacturer,

François Coty.

Château de la Filolie, July 2017

On Sunday, 17 August, the two poets walked on to Brantôme, where Pound sent another postcard back to Dorothy at the Hotel Poujol in Excideuil (PFP 26) -

Brantome reached & pleasing. T.

has 7 blisters. Will probably proceed by train tomorrow. Sunday 5.30 pm.

Postcard

of Brantôme written by Ezra Pound on 17 August 1919 to Dorothy at the Hotel

Poujol in Excideuil

Baedeker (42)

described Brantôme as -

...prettily situated on the Dronne.

It possesses the interesting remains of an old Benedictine Abbey, dating from

the days of Charlemagne, and once owned by the chronicler Pierre de Bourdeilles

(ca 1527 - 1614) who assumed its name. The Romanesque

Tower , standing on a sheer rock

honeycombed with caverns, is one of the oldest in France

Pound had been to Brantôme before - in 1912, in the

rain.

The former

Benedictine Abbey at Brantôme, April 2015

Despite Eliot's

seven blisters, and possibly due to the efficacy of le papier Fayard, they walked on from Brantôme to Bourdeilles. On 22 August, on letterhead of the

Grand Hôtel de Bordeaux, Pound wrote (L/HP, 446) -

Walking tour Thiviers: Brantome:

Bourdeilles. Eliot went on to the Fonts de Gaume & Les Eyzies grottes -

prehistoric painting and sculpture. Must take a week to same, sometime.

The station at Valleuil-Bourdeilles at

which Pound and Eliot

probably ended their 16-18 August 1919

walking tour[21]

The polychrome paleolithic paintings of Font de Gaume had

been discovered in 1901 and were already famous, although they were not

mentioned by name in the contemporary Baedeker.

A 21st century postcard of the Magdalenian

wall paintings at Font de Gaume

Did Pound ever make it to Les Eyzies and Font de Gaume?

Perhaps he did in 1923[22],

though he referred to the caves of Les Eyzies as early as 1920 or 1921 in a

draft Canto (PC, 27) -

At les Eyzies, nameless drawer of panther,

So I in a narrow cave, secret scratched on a wall...

On the damp rock, is my panther, my aurochs scratched in obscurity.

He seems to have been relying on Eliot's impressions of the

caves and postcards. His handwritten notes from Pisa

so his eminence, the eminent

Possum

visited

Dordogne cavernes

& our eminent confrere

mistrusted

the

authorship & antiquity

of the designs on postcards. -

but if not Picasso -

who faked 'em.

In Canto LXXIV this became -

I have

forgotten which city

But the

caverns are less enchanting to the unskilled explorer

than the

Urochs as shown on the postals... (LXXIV/448)

Pound could,

however, equally have had in mind when he wrote these lines a postcard that

Nancy Cunard sent to him from Les Eyzies in October 1923. That postcard shows a

line drawing of a mammoth copied from the caves at Font de Gaume.

From Bourdeilles

Pound returned to Excideuil to begin packing up for the journey back towards London

The sketch

map on the back of a 1919 Thiviers postcard in the Pound Family Postcard

collection. It shows the station at Les Eyzies, the caves at Font de Gaume and

the castles of Commarque and Laussel.

In the Hamilton College

In December 1911,

a human figure, estimated at 25,000 years old, was discovered at Laussel carved

into the limestone and painted in red ochre. The so-called Venus of Laussel is

a representation of a female, probably pregnant, holding a horn aloft in her

right hand.[25]

This bas-relief carving is one of the oldest known artistic representations of

the human form. As such it stands right at the beginning of the "mind of

Europe", several millennia earlier than the cave paintings of the

"Magdalenian draughtsmen" of Font de Gaume and Lascaux .

It is a place that would likely have attracted Eliot.

Venus of Laussel

Two months later,

back in London

And as it is certain that some

study of primitive man furthers our understanding of civilized man, so it is

certain that primitive art and poetry help our understanding of civilized art

and poetry. Primitive art and poetry can even, through the studies and

experiments of the artist or poet, revivify the contemporary activities. The

maxim, Return to the sources, is a good one.

Eliot's interest

in "primitive man" would resurface in The Waste Land with its references to Jessie Weston's From Ritual to Romance (1920) and J. M.

Frazer's The Golden Bough (1890).

It seems likely

that Eliot then made his way eastward from the Les Eyzies area to Brive, in

Corrèze, the département that abuts Dordogne to the east. I suggest that he was in Brive,

again with Ezra and Dorothy, by 22 August.[26]

After Pound

returned from Bourdeilles to Excideuil on 18 or 19 August, he and Dorothy made

their way to Brive. They were in Brive on 22 August when Ezra wrote to his

mother on the letterhead of the Grand Hôtel de Bordeaux (L/HP, 446) -

On our way north - with

contemplated delays. Malamort and Aubazine one hopes tomorrow. Then back here

& to Orleans Paris

Today Malemort

("And Malemort keeps its close hold on Brive" - Near Perigord) is a suburb of Brive, surrounded by sprawling

out-of-town shops and fading, light-industry factories. Then it was "a

little village on the hem of the mountains. Leaving the meadows behind us, we

climb the hill and find ourselves at once in the Middle Ages" (Smith,

211). The Romanesque church

of St Xantin

By river-marsh, by galleried

church-porch,

Malemorte, Correze... (VI/22)

The church dates

from the twelfth century. The presbytery or priory, along which the galleried

church-porch is built, is of a slightly later date. The galleried church-porch

is, apparently, a nineteenth century addition. The church of St Xantin

The galleried church-porch

at St Xantin at Malemort-sur-Corrèze, March 2018

Malemort owes its

name to a massacre there in the times of Richard Coeur de Lion. On 21 April

1177, "two thousand persons - free-lances, their wives and their children

- were slain here in one day" (Smith, 211). In 1912, Ezra Pound had

resisted the temptation to visit Malemort (WTSF, 35) -

There is to the east of Brive a

place with so fine & sinister a name that I was almost led there, altho I

knew there was nothing for the eye, a name I had invented for a poem once but

had never expected to find in the stone as Malemort. I restrained myself

however from this defection & took the jagged highway toward Toulouse

Aubazine, farther

away and high in the hills, is the site of two nearly adjacent monasteries - one

for men and one for women - dating from the 12th century. Of slightly earlier

independent foundation, the monasteries at Aubazine joined the Cistercian order

in 1147.

The church of the Cistercian abbey at Aubazine, July

2017

It would seem that

the hopes of visiting Malemort and Aubazine that Ezra expressed in his 22

August letter were fulfilled, and it seems probable that Eliot went for the

walk to Malemort and Aubazine with him, for on 23 August Dorothy sent a

postcard from Brive (PFP 51) -

We expect to leave tomorrow late,

for Orléans. The two men have gone for a walk, but I couldn't face it... Still

very hot.

Postcard

sent by Dorothy from Brive on 23 August 1919

I suggest that the

reason the second postcard no. 5 (of the Château de Thiviers with the sketch

map on the back) found its way into the Hamilton College Collection is that

Eliot gave it to Ezra and Dorothy Pound in Brive in case they should ever want

to make good on Ezra's notion of taking a week to visit "Fonts de Gaume & Les Eyzies grottes

- prehistoric painting and sculpture".

Soon afterwards,

probably on 25 August, Eliot wrote a postcard to Lytton Strachey (LTSE1, 388) -

I have been walking the whole time

since I arrived and so have had no address at all. Through Dordogne

and the Corrèze, sunburnt - melons, ceps, truffles, eggs, good wine and good

cheese and cheerful people. It is a complete relief from London

As Eliot did not

arrive back in London

"My

lady of Ventadour

"Is shut by Eblis in

"And will not hawk nor hunt

nor get her free in the air... (VI/22)

As Canto VI was

ready soon after Pound returned to Britain ,

it could well be that he discussed it with Eliot during their time in France

Ussel lies beyond

Ventadour itself when coming from Brive.

Dorothy and Ezra

left Brive on the overnight train to Orléans on 24 August. On 26 August, from

Orléans, Dorothy sent another postcard to her mother (PFP 87) -

Tuesday

We got here yesty. morning for a

break: had quite a good journey up, with plenty of fresh air in the carriage.

Its a pleasant town, with a few old houses & the worst cathedral I have

ever seen... We leave tomorrow morn: for Paris

Postcard sent by Dorothy to her mother on 26 August

1919 from Orléans

From Orléans they

went on to Paris on 27 August and from Paris

...we have a large room from which

we see the Seine & Pont Royal and a corner of the Louvre & windows of

rue de Rivoli, on the opposite side.

Mildly expensive, but Excideuil has

been an economy.

Food here rather cheaper than in London

By 11 September,

they were back in London

Ezra Pound's aim

of putting TS Eliot through a cure during his holiday in France London France France

*

Excideuil found

its way more than once into Ezra Pound's poetry. In addition to the lines from Provincia Deserta, quoted above, there

are these lines from the much-later 1945 Pisan Cantos -

Whither go all the vair and the

cisclatons

and the wave pattern runs in the

stone

on the high parapet (Excideuil)

Mt Segur and the city of Dioce

Que tous les mois avons

nouvelle lune. (LXXX/530)

Earlier, three

years after his days in Excideuil, he wrote the following lines as part of a

draft of the Malatesta Cantos (quoted in Moody 1993, 81) -

As

we had sat, three of us at Excideuil

over Borneil's old bake-oven

...that was three years ago...

on the roman mound

level

with the town spire,

"e poi gli affina" for

you.[28]

Clearly, the

reference to the "three of us at Excideuil" refers to the time Eliot

spent there with Ezra and Dorothy in the summer of 1919. Borneil is, of course,

Giraut de Borneil, who came from Excideuil.[29]

His toponym - de Borneil - is probably taken from a small hilltop hamlet just

to the east of Thiviers now known as Bourneix or Bournay. He is said to have

been the son of one of Excideuil's bakers (Thibaud, 61), an association Pound

picked up in these lines.

There is an unpretentious monument to Giraut de

Borneil in Excideuil, but it is easy to overlook it. It sits on the edge of a

car park just outside the outer gate to the castle where today Ezra Pound's

"wave pattern runs in the stone".

From the monument

to Giraut de Borneil in Excideuil, July 2017

The line "e poi gli affina" for you, no

doubt bears some reference to the subject of

discussion in Excideuil and, as we shall see, to Eliot's state of mind

in particular. It comes from Dante's Divine

Comedy "Purgatorio" Canto XXVI, a Canto featuring the shade of

Arnaut Daniel and quoted by both Pound and Eliot in their own work. Eliot

adopted the full final line of the Canto (Poi

s'ascose nel foco che gli affina) as line 428 of The Waste Land. The two poets honorifically called each other

"Arnaut" - Eliot implicitly in dedicating The Waste Land to Ezra Pound, "il miglior fabbro"[30]

; and Pound when he referred to Eliot a "Arnaut" in his Canto XXIX.

In Pound's Canto

XXIX, "Arnaut", the "wave pattern that runs in the stone",

and the town spire on the same level as the well-curb in the castle courtyard

appear together -

So Arnaut turned there

Above him the wave-pattern cut in

the stone

Spire-top alevel with the well-curb

And the tower with the cut stone

above that, saying:

'I

am afraid of the life after death.'

and after a pause:

'Now, at last, I have shocked him.'

(XXIX/145)

The line -

"So Arnaut turned there" - might hold a reference to the first line

of Eliot's poem Ash Wednesday (Eliot

1969, 89) - "Because I do not hope to turn again...".[31]

Pound's use of the verb "turn" is anyway significant.

"Turn" is commonly used to refer to religious conversion. The

traditional words pronounced as ashes are received on the forehead at the

beginning of Lent are "Turn away from sin and be faithful to the gospel",

echoing biblical uses, for example in 1 Thessalonians 1:8 (AV/KJV) "...and

how ye turned to God from idols to serve the living and true God." In the Hebrew Bible, the word translated as repent is shub, literally to turn. Schuchard

(3) has suggested that "the suffering poet [Eliot] conceived of himself as

Arnaut, his lustful soul wrapped in purgatorial flames." Here too perhaps

is the significance of Pound's reference to Dante's - "e poi gli affina for you" -

refining fires in the Purgatorio

Canto XXVI where the shade of Arnaut Daniel features.

Despite the

lighthearted tone of Pound's 1965 elegy for Eliot and the shining accounts in

Eliot's letters immediately following the trip, we have here in these lines -

purgatorial flames, "I am afraid of the life after death" - more than

a hint that the August 1919 holiday in the Périgord was, for Eliot at least,

not just a matter of jokes and blisters. Bush (211) suggests that the poets

discussed James Joyce's Ulysses, then

coming out in serial publication with Pound's help. Eliot had brought with him

to France Toulouse on

29 May 1919, Pound wrote a postcard to his mother-in-law asking her to send

"the 'razo' (an [sic] nothing else) of the Arnaut Daniel to T.S. Eliot at

18 Crawford Mansions Crawford St.

Place du Marché

(Place Bugeaud) in Excideuil,

showing

the church spire as it was when Pound and Eliot stayed in the town

In this passage

from Canto XXIX where Pound probably accurately describes his friend's state of

mind and quotes his words, he is also precise and accurate in his geographic

references. If you stand in the courtyard of Excideuil's castle and look north

you are indeed level with the top of the church tower rising from the centre of

the town below. Today, however, the ancient church of St Thomas

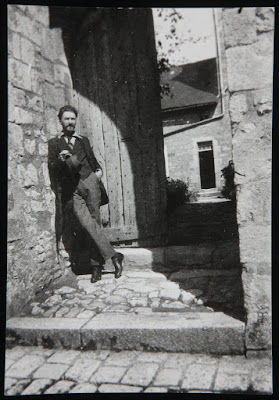

The ruins of the château at Excideuil in 1919. Dorothy's notes on the

back

of the postcard read "Several days here - TSE joined us."[33]

At the time Pound

and Eliot were in Excideuil, the castle on its cave-pitted crag was

semi-derelict. In 1971, Hugh Kenner wrote "...at semi-ruined Excideuil a

wave pattern's lilt in the stone on the high parapet proclaims an eternal form

educed from flux..."; and by way of a footnote added, "As of 1919.

Later the castle crumbled, and still later its restorers fitted stones at

random. In 1970 the only discoverable block of wave pattern had been placed

near the top of the left-hand gatepost" (Kenner castle of Excideuil

The

"wave-pattern cut in the stone" at Excideuil, March 2017

*

Périgueux, capital

of Dordogne , lies southwest of Excideuil along

the valleys of the Loue and the Isle. In 1919 a steam tramway connected the two

towns.

Both Pound and Eliot seem to have found in Périgueux (which Pound

usually refers to as "Perigord") part of a disturbing vision or

experience. Here are Pound's lines in Provincia

Deserta -

I have walked

into

Perigord

I have seen the torch-flames,

high-leaping

Painting the front of that church;

Heard, under the dark, whirling

laughter.

I have looked back over the stream

and

seen the high building,

Périgueux, looking "back over the stream",

July 2017

The bright white

stone of the Cathedral of St. Front at Périgueux rises above the tiled roofs of

the surrounding town. Pound in 1912 was enthusiastic - "what a cathedral!

Be on your guard San Marco, here are domes against your domes, & a tower

along your tower..." (WTSF, 19). The church's cupolas and magnificent

bell-tower are all surmounted by lanternons

that look uncannily like the medieval lanternes

des morts of the Périgord and hark back even further to the funerary towers

of antiquity. In the dark, faintly illuminated by torchlight from below, they

could easily appear like the long white shafts of minarets.

Later, in Canto

LXXX, Pound would liken Périgueux to New York

- "But that New York

Périgueux[34]

Eliot's experience

in Périgueux was perhaps the more profound. He referred to it in a letter of 9

August 1930, more than a decade after the 1919 walking holiday and eight years

after The Waste Land had been

published. He wrote to William Force Stead[35],

whose The House on the Wold had just been published, that his

friend's new volume of verse (LTSE5, 287) -

expresses those feelings that I have

known but never seen so well expressed.

This sense of dispossession by the dead I have known twice, at Marlow and at Perigueux.

From the opening

lines of The Waste Land's first

section (The Burial of the Dead), and

running through the whole of the poem, there is powerful sense of death and

dispossession (Eliot 1969, 61) -

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

There is death and dispossession

too in the closing lines of The Waste Land where Eliot quotes from Gérard de Nerval's El Desdichado - "Le Prince d'Aquitaine à la tour abolie"

(Eliot 1969, 75) -

Je suis le

Ténébreux, - le Veuf, - l'Inconsolé,

Le Prince

d'Aquitaine à la Tour abolie :

Ma seule Étoile est morte, - et mon luth constellé

We know of three

visits Eliot made to Périgueux - in the winter of 1910/11, his early morning

arrival on 9 August 1919, and another visit some ten days later after leaving

Pound at the end of their walk from Excideuil to Bourdeilles. Based Pound's

lines in his Canto XXIX - "I am afraid of the life after death" - and

what we know of Eliot's state of mind in 1919, it seems appropriate to relate

the second episode of "dispossession by the dead" to one of his

August 1919 visits.[38]

Death did surround

Eliot in the summer of 1919 and was prominent then in his thoughts, memories

and inspiration. Eliot's father had died earlier in the year - on 7 January

1919 - of an unexpected heart attack. Influenza - "Kansas France

Eliot had lost

many friends in the War, including his two of his closest French friends from

his 1910-11 year in Paris Paris Dardanelles

in the war?" (108).

War

memorial at Hôtel Dieu on the Ile de la Cité in Paris

showing

the name of Jean-Jules Verdenal, March 2017.

August 1919 was

Eliot's first return to France

On Eliot's

"sense of dispossession by the dead", John Worthen wrote -

Eliot subsequently wrote about the

feeling of dispossession on a number of occasions. In The Family Reunion, Harry describes "that sense of separation,

/ of isolation unredeemable, irrevocable"; in "East Coker",

Eliot imagined the "fear of possession" of old men. "Of belonging to another, or to others, or to

God." Being "possessed" - taken over, completely, so that you

are dispossessed of your old self and attachments - is terrifying but (for

Eliot after 1927) would have been the only real solution to life's problems. In

1940, he would go so far as to announce that "You must go the way of

dispossession". That "way" involved Christian conversion. (93)

Without using the

term "dispossession", Eliot in 1935 wrote about a terrible awareness

of isolation without God (Schuchard, 120) -

There are moments,

perhaps not known to everyone, when a man may be nearly crushed by the terrible awareness of his isolation from

every other human being; and I pity him

if he finds himself only alone with himself and his meanness and futility, alone without God. It is after these

moments, alone with God and aware of our worthiness, but for Grace, of nothing but

damnation, that we turn with

most thankfulness and appreciation to the awareness

of our membership: for we appreciate

and are thankful for nothing fully

until we see where it begins and where it ends.

Eliot was not the

only literary figure in Britain

Give up yourself, and you will find

your real self. Lose your life and you will save it. Submit to death, death of

your ambitions and favourite wishes every day and death of your whole body in

the end: submit with every fibre of your being, and you will find eternal life.

Keep back nothing. Nothing that you have not given away will be really yours.

Nothing in you that has not died will ever be raised from the dead. Look for

yourself, and you will find in the long run only hatred, loneliness, despair,

rage, ruin, and decay. But look for Christ and you will find Him, and with Him

everything else thrown in. (189)

It would seem then

that not only The Waste Land, but

also Eliot's turning - "So Arnaut turned there" - to Christianity,

was beginning to take shape in August 1919, and marked by Ezra Pound with

topographic precision at Excideuil by (XXIX/145) -

...the wave-pattern cut in the

stone

Spire-top alevel with the well-curb

Excideuil,

May 2010

Showing

the 1936 crown on the church tower

"Spire

top alevel with the well-curb

And the

tower with the stone cut above that"

Later these

seminal milestones in Eliot's life - the beginnings of The Waste Land and his conversion to Christianity - were recalled

by Ezra Pound through a reference to Excideuil in his brief elegy after his

fellow poet's death.

*

In Pound's Canto LXXIV - the first of the Pisan

Cantos - we read -

and at Limoges

bowed

with such french politeness "No that is impossible."

I have

forgotten which city

But the

caverns are less enchanting to the unskilled explorer

than the Urochs as shown on the

postals,

we will

see those old roads again, question,

possibly

but

nothing appears much less likely,

Mme

Pujol,

Madame Pujol is another of Pound's memories of

Excideuil. Hers is one of the very few twentieth-century personal names from

Pound's 1912 and 1919 travels in France

On 1 June 1920, Pound

wrote from Sirmione, "...considering how Excideuil tempted me last summer

(with of course the distinction that Excideuil had Madame Pujol in the village

and the french do know how to cook..." (L/JQ, 180). In 1912, Ezra Pound had stayed at the Hôtel

Poujol - spelling the family name correctly in the notes on that journey, as,

indeed, he and Dorothy did on the postcards of 1919. He described his 1912

arrival in Excideuil thus -

...I would fain have dragged my remains

to rest in the next valley, at Savignac-les-églises, at an inn there, but this

inn being filled with a captain & three men @ arms I took the tramway for

Excideuil in that prescience which occasionally descends when after we have

done our utmost the perfect thing awaits. (WTSF, 23)

As we have seen,

he was sufficiently impressed to return for a longer stay, with his wife,

Dorothy, in 1919.

Carroll Terrell,

in a footnote to Canto LXXIV writes: "Mme Pujol: A landlady in Provence Limoges

Louise Poujol (née Delprat)[42]

was born in Montignac in 1869 and grew up in Périgueux where she married

François Poujol in 1893. They came to Excideuil in the early years of the

twentieth century, probably about 1904, after several years living in Brive-la-Gaillarde

Between Pound's

first visit to Excideuil and his second, François Poujol had died - aged 50, in

1917. One of the couple's sons, René, had died a year later - aged only 18;

another, Roger, had been wounded in the war.[43]

Yet another son, Jean-Dominique, is listed as a cook in the years immediately

following the Great War, following in his father's footsteps. By August 1919,

Madame Poujol was a grandmother. Dorothy Pound recorded on a postcard that she

wrote to her father from Excideuil on 15 August 1919, the day before her

husband and TS Eliot set off walking to Thiviers (PFP pc not numbered) -

Have helped to paint a

"cot" for the patronne's grandchild! Otherwise it is too hot to move

much. Our room is well decorated with flypapers - & we have introduced one

into the kitchen.

All the Excideuil

archive listings for the Poujol family's address are in rue Gambetta. There

were no house numbers on the streets in those days. Nor was there, apparently,

a hotel in Excideuil formally called "Hôtel Poujol". There were,

however, two hotels in the rue Gambetta in Excideuil in 1919 - the Hôtel

Mordier (or Central) and the Hôtel Chatelier (or Métropole). There is no

certain memory today as to which of these two establishments was run by the

Poujol family in the early years of the twentieth century and to which their

name seems to have been informally attached. Opinion seems to come down broadly

in favour of the Hôtel Chatelier. Hôtel Chatelier (Métropole) had a large

garden - perhaps the one where TS Eliot sat on arrival in Dordogne

in August 1919.[44] A

case for the Hôtel Mordier can, however, be made based on its reputation for an

excellent cuisine. Pound recorded appreciating the cooking at the place he

stayed Excideuil. If the hotel and garden mentioned in his letter to his mother

of 14 October 1919 refer to Excideuil, so did Eliot. Neither location serves

any longer as a hotel.

Hôtel Mordier, Excideuil[45]

The building that

was once Hôtel Mordier sits, without distinction of any sort, on a corner

between two streets just to the east of the old Porte des Cordeliers and

opposite Excideuil's war memorial and the hospital which occupies the remaining

buildings and site of the Couvent des Cordeliers. The building that housed the

Hôtel Mordier functions now as the office of an insurance company.

The Hôtel

Chatelier was just along the street (then an extension of Avenue Gambetta, now

Avenue Eugène Le Roy) to the east, facing south down the Promenade. The

Promenade now doubles as the Allée André Maurois.[47]

André Maurois lived at the Château d'Essendiéras, just to the northeast of

Excideuil. Today, at the far end of the Promenade, overlooking the by-pass and

the former route of the train to Hautefort, is a statue of Maréchal Bugeaud

that once stood in the Place d'Isly in Algiers

Postcard of the Promenade in Excideuil with the

Métropole at its north end

On the evening of

28 June 1944, the occupying German forces raided Excideuil, which was regarded

as a centre of the Résistance. When they moved on the next day, the Hôtel

Chatelier was in flames (Vaugrenard, 61 et seq.). By the time the fires were

put out, the Hotel Châtelier had been completely gutted. That proved to be the

end of the building's vocation as a hotel.

Ezra Pound (WTSF,

28) -

At the hotel of Poujol I

came also upon this adv. worthy of memory:

sic transit

gloria.

*

How could Louise

Poujol, a widowed innkeeper in a small town in rural France Dordogne holiday of 1919 would serve

to crystallize the composition of The

Waste Land and that memories of those days would resurface in the Cantos over the coming decades?

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AV/KJV - The Authorised (King

James) Version of the Bible.

EESP - Excideuil et son Pays. Excideuil: Editions de la Tuilière, 1997. Print.

LE - Pound, Ezra. Literary Essays of Ezra Pound. Ed. T.S.

Eliot. London

L/HP - Pound, Ezra. Ezra Pound to his Parents: Letters 1895 -

1929. Eds. Mary de Rachewiltz, A. David Moody and Joanna Moody. Oxford

L/JQ - Pound, Ezra. The Selected Letters of Ezra Pound to John

Quinn, 1915 - 1924. Ed. T. Materer. Durham ,

NC

LTSE1 - Eliot, T.

S. The

Letters of T.S. Eliot, Volume 1, 1898-1922, Revised Edition. Eds. Valerie

Eliot and Hugh Haughton. London

LTSE3 - Eliot, T.S. The Letters of T.S. Eliot, Volume 3,

1926-1927. Eds Valerie Eliot and John Haffenden. London

LTSE5 - Eliot, T. S. The Letters of T.S. Eliot, Volume 5,

1930-1931. Eds. John Haffenden and Valerie Eliot. London

P - Pound Ezra. Personae, The Shorter Poems. Eds. Lea

Baechler and Walton Litz. New York

PC - Bacigalupo, Massimo. Posthumous Cantos. Manchester

PFP - Hamilton College

WTSF - Pound, Ezra. A Walking Tour of Southern

France : Ezra Pound Among the Troubadours. Ed. Richard

Sieburth. New York

OTHER WORKS CITED

Bacigalupo, Massimo.

"Tradition in 1919: Pound and Eliot."

T.S. Eliot and the Concept of

Tradition, Eds. Giovanni Cianci and Jason Harding. Cambridge

Baedeker, Karl. Southern France including Corsica ,

5th edition. Leipsic: Karl Baedeker, 1907. Print

Bressan, Eloisa.

"Reading A Walking Tour in Southern

France... in Southern France : A

Geographical Approach." Make It New

2.1 (2015): 77-86. Digital.

Bressan, Eloisa.

"Regionalism and Mythmaking: A Map for Ezra Pound's Walking Tour in Southern France , 1919." Make It New, 2.4 (2016): 44-55. Digital.

Bush, Ronald L. The Genesis of Ezra Pound's Cantos.

Princeton: Princeton

University

Capitan, Louis and Breuil, Henri. "Les figures peintes à l'époque

paléolithique sur les parois de la grotte de Font-de-Gaume (Dordogne)." Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des

Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 47.2 (1903).

Conover, Anne. Olga Rudge and Ezra Pound: "What Thou

Lovest Well...". New Haven : Yale University

Crawford, Robert. Young Eliot: From St

Louis to The Waste

Land

Dunez, Paul. Excideuil au Pays des

Troubadours. Périgueux: IFIE Editions Périgord, 2013. Print.

Eliot, T.S. "Tradition

and the Individual Talent." The

Egoist, September 1919. Print.

Eliot, T.S. "War-paint

and Feathers." The Athenaeum. 17

October 1919. Print.

Eliot, T.S. The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot. London

Eliot, T.S. The Poems of T.S.

Eliot, Volume 1, Collected & Uncollected Poems. Eds. C. Ricks and J. McCue.

London

Le Guide Dordogne Périgord. Périgueux: Fanlac, 1994. Print.

Hargrove, Nancy D. T.S. Eliot's Parisian Year. Gainesville : University

of Florida

Hemingway, Ernest. A Moveable Feast, The Restored Edition. London : Jonathan

Cape

Holroyd, Michael. Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography,

Volume 2, The Years of Achievement (1910-1932). London

Kenner, Hugh. The Pound Era. Berkeley

and Los Angeles : University of California

Lewis, C.S. Mere Christianity, London

McGrath, Alister. C.S. Lewis: A Life. London: Hodder &

Stoughton, 2013. Print.

Le Maitron. Dictionnaire biographique

du mouvement ouvrier français. (http://maitron-en-ligne.univ-paris1.fr/spip.php?article127149,

notice POUJOL Roger, Hippolyte par Claude Pennetier, version mise en ligne le

30 novembre 2010, dernière modification le 1er mai 2016). Digital.

Miller, J.E. T.S. Eliot, The Making of an American Poet,

1888-1922, University Park , PA : The Pennsylvania

State University

Moody, David A. "Bel

Esprit and the Malatesta Cantos: A Post-Waste Land Europe . Eds. Richard Taylor and

Claus Melchior. Rodopi, 1993.

Moody, David A. Ezra Pound: Poet: A Portrait of the Man and

his Work, I: The Young Genius, 1885-1925. New York: OUP, 2007. Print

Penaud, Guy. Dictionnaire

des Châteaux du Périgord. Périgueux: Editions du Sud-Ouest, 1996. Print.

Penaud, Guy. Les Troubadours

Périgordins, Périgueux: Editions de la Lauze, 2001. Print.

Perinot, Claude. "Jean Verdenal, An Extraordinary

Young Man: T.S. Eliot's Mort aux Dardenelles." South Atlantic Review, Vol. 76, No. 3 (Summer 2011). 33-50. Print.

Pompidou, Georges. Anthologie de la

Poésie française. Paris: Hachette (Livre de Poche), 1961. Print.

Pound, Ezra. The Cantos of Ezra Pound. New York

Pound, Ezra. "For

T.S.E." The Sewanee Review 74.1

(1966): 109. Print.

Schuchard, Richard. Eliot's Dark Angel. Oxford

Shakespear (Pound), Dorothy. Etruscan Gate. Ed. M. Merchant. Exeter

Smith, Justin. The Troubadours at Home, Volume 2. New York

Spender, Stephen. Eliot. London :

Fontana

Terrell, C.F. A Companion to the Cantos of Ezra Pound.

Berkeley and Los Angeles :

University of California

Thibaud, Pierre. L'Auvézère et La

Loue. Périgueux: Fanlac, 1993. Print.

Vaugrenard, Alain. Excideuil, Les

Années Noires, 1939/1946. Périgueux: IFIE Editions Périgord, 2012. Print.

Wilhelm, J.J. Ezra Pound in London

and Paris University Park , PA : The Pennsylvania

State University

Worthen, John. T.S. Eliot: A Short Biography. London

[1] Le papier Fayard was a patent treatment for

blisters and corns. For Eliot and Pound, August 1919 (not 1920 or 1921 as Pound

- perhaps mischievously - recollected)

was, at least in part, a walking holiday.

[2] There is

no inscription on the back. Although Ezra Pound was at Châlus in 1912, there is

no suggestion that he revisited it in 1919. (Note that the date on the front of

the postcard should be 1199 rather than 1198.) Some of the postcards in the

Hamilton College Collection of Pound Family Postcards (PFP) appear to have been

collected by Ezra Pound in 1912.

[3]? On the back of PFP 590, Dorothy’s

green ink records – “EP. D.P. We walked into Foix, flags flying. Armi Peace

just signed 1919.” The Versailles Treaty was signed on 28 June.

[5] The 5th

edition (1907) was still the most recent in 1919.

[6] Ezra

Pound wrote in Near Perigord -

Tairiran held hall in

Montignac,

His brother-in-law was all

there was of power

In Perigord, and this good

union

Gobbled

all the land, and held it for some hundreds years.

[7] "En Bertrans" took his toponym from, and

probably born at, the Château de Born (or de Bellegarde) about eight kilometres

to the northeast of Hautefort. Smith tried to find "the

original Born castle ... not far from Dalon, in the forest above the lake of Born castle

of Bertrand de Born

[8] On his

1912 walking tour, Pound's route between Hautefort and Excideuil seems to have

been somewhat circuitous. He seems to have retraced his steps eastward from

Hautefort to explore the country between Périgueux and Hautefort, travelling

along the valley of the Auvézère, visiting Blis-et-Born in the hills, and

possibly Auberoche as well as Cubjac in the Auvézère Valley

[9]

Source:

Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, King's College, London

[10]

"...to Montignac. Thither went Bertran de Born, too, but not by a route so

indolent, for at the end of the journey in a lofty castle butressed by a

natural pillar of black ivy-wreathed stone forty feet high, and boldly

overlooking the town and the river, Lady Maent, a sister of Maria de Ventadorn

(or Ventadour), waited to smile upon him" (Smith 223). Maent, married to a brother of the Count of

Périgord, Maria de Ventadour and a third sister, Elis

[11] A

railway line formerly ran from Hautefort to Gourdon via Terrasson, Montignac

and Sarlat. I have not been able to trace "les Prunes" on this route.

[12] The

three walks were probably Hautefort to Montignac, Sarlat to Souillac, and

Souillac to Rocamadour.

[13] For

example, WTSF, 32, and Terrell Vol. 1, 111. Wilhelm 232 gives a precise date -

28 July 1919 - and writes, "They took a long side trip [from Excideuil]

northeast to Clermont where the First Crusade was announced. Along the way,

they passed through Ussel, the home of at least three troubadours. On a side

road that was difficult to locate, they found the high windswept ruins of Ventadorn/Ventadour..."

Bressan 2016, on the other hand, does not include Ventadour or Ussel in the

1919 itinerary.

[14] The

August 1923 trip was also a walking trip - "...walking 25 kilometers a day

with a rucksack..." (Olga Rudge, quoted in Conover, 7). "No written record remains of that

summer holiday, or their itinerary, only a fading black-and-white photograph

album labelled 'August 1923 - Dordogne '. Olga

was the photographer and Ezra often the subject, appearing under gargoyles of

the cathedrals in Ussel and Ventadour and other unidentifiable French

villages." (Conover, 7). Curiously, the book reprints one of these

photographs with the caption Ezra Pound

in the neighborhood of Ventadour, Summer 1919. Photograph by Olga Rudge. Yet

Pound only "...met Olga in the fall of 1922..." (Conover, 1).

[15] PFP

156. This postcard was sent by Miss N. Juillet to Dorothy Pound on 21 July

1924.

[17] The

Magdalenian era of the late Upper Paleolithic runs from about 17,000 years ago

to about 12,000 years ago. It takes its name from Abri de la Madeleine, a rock

shelter in the Vézère valley near the village of Tursac

[18] It is

unclear from the letter whether this hotel, lunch and garden were in Périgueux

or Excideuil. It would seem likely that Pound would have wanted to go back to

his hotel in Excideuil where he was staying with Dorothy; although, if that

were the case, it would probably have made more sense for Eliot to have changed

trains in Thiviers for Excideuil rather than in Périgueux.

[19] Source: https://fr.geneawiki.com/images/thumb/4/47/24164_-_Excideuil_-_Gare_Tramways.JPG

[20] TS

Eliot worked for Lloyd's Bank from 19 March 1917 to 25 November 1925. Ezra

Pound continued to be concerned for Eliot's well-being working in a bank after

their days in Excideuil. Ernest Hemingway (177) wrote, "Ezra Pound was the

most generous writer I have ever known and the most disinterested. He was

always doing something practical for poets, painters, sculptors and prose

writers that he believed in and would help anyone, whether he believed in them

or not, if they were in trouble. He worried about everyone and in the time when

I first knew him he was most worried about T. S. Eliot who, Ezra told me, had

to work in a bank in London

[21] Source:

www.cfpa.asso.fr/images/Gares/gare10603.jpg

[22] In

August 1923, Ezra Pound revisited Dordogne

with Olga Rudge. He may have visited Les Eyzies then. Other than visits to Ventadour

and Ussel (in Corrèze) little is documented with geographic precision

concerning this trip.

[23] The

original of this postcard is held in the Lilly Library, (Ezra Box 1 Pound mss:

Nancy Cunard), Indiana University , Bloomington ,

Indiana

[24] Pound

would have been able to return to Excideuil by train/tram by one of two routes

- either (with Eliot) via Périgueux or via St. Pardoux and Thiviers.

[25] The

Venus of Laussel is now on display in the Musée de l'Aquitaine in Bordeaux Berlin

[26] In his

correspondence, Eliot wrote of August 1919 as a walking holiday. To Lytton

Strachey he wrote, "I have been walking the whole time..." (see

below). To his mother he wrote that he "spent part of my vacation with him

[Pound] in the village

of Excideuil

[27] It

seems unlikely that Eliot would not have dutifully sent postcards to his wife,

Vivien, while he was in France France

[28] When

the Malatesta Cantos were published (The

Criterion, Vol. 1, No. IV, July 1923, "Malatesta Cantos (Cantos IX to

XII of a long poem), by Ezra Pound), these lines were omitted. TS Eliot was the

editor of The Criterion.

[29] There

is actually some doubt as to where Giraut de Borneil was from. While he is

probably from the region of Excideuil in Dordogne, it is possible that he was

from the area of Exideuil on the borders of Charente

and Haute-Vienne (Penaud 2001, 69). There are also several hamlets called

Bourneix in the region.

[30] This is another

reference from Dante's "Purgatorio" Canto XXVI to Arnaut Daniel,

"il

miglior fabbro del

[31] The

first part of "Ash Wednesday" was published in Commerce in Spring 1928 quoting Guido Cavalcanti, "perch'i no spero di tornar giammai".

Pound's Canto XXIX was published in 1930.

[32] On 6

August 1919, shortly before he left London for France France

[33] PFP.

Postcard not numbered.

[34] PFP 19.

Dorothy's later note on the back reads "Did I see this? EP anyway knew

it." It might seem strange that Dorothy might not have seen Périgueux in

the summer of 1919, but it is certainly not impossible. The journeys that we

know of that Ezra and Dorothy took together from Excideuil were to the

southeast, with the exception of the possible trip to Poitiers

[35] Like Pound and Eliot, William Force Stead

(1884-1967) was an American. He came to England

in the US Oxford United States

[36] Commentators (for example

see Eliot 2015), though not Eliot’s own Notes

on the Waste Land (Eliot 1969, 76), often cross refer the reader to

Chaucer’s opening lines of the Prologue to The

Canterbury Tales: “Whan that aprill with his shoures soote...” But,

while in the Périgord, one might also look to the following lines from Pierre

de Bussignac, a 12th century Périgourdin troubadour associated with Hautefort -

Quan lo dous tems d'abril

fo'ls arbres secs fulhar,

e'ls auzelhs mutz cantar

quascun en son lati...

When April's sweetness

Brings leaves again to the

dry trees

And the silent birds begin

to sing

Each in its own tongue...

My translation. For Pierre de

Bussignac, see Penaud 2001 77.

[37] While the primary

reference for de Nerval's "la Tour abolie" is probably to a Tarot

card, it is interesting to note in passing that de Nerval believed himself to

be descended from a noble family in Aquitaine

with a castle on the banks of the Dordogne , a

patrimony from which he was dispossessed.

[38] Some

commentators (for example, Wilhelm, 235) place Eliot back in Excideuil on 21

August 1919, thereby dating the line "I am afraid of the life after

death" to after the Périgueux episode of "dispossession by the

dead". It is not clear to me that Eliot did return to Excideuil after the

walking trip with Pound to Thiviers, Brantôme and Bourdeilles.

[39] Eliot may

have passed through France

on his way to Marburg Pau London to Marburg

is through Belgium and we

know that Eliot visited Bruges , Ghent

and Brussels Germany

after the outbreak of war in August 1914 - through the Netherlands to London ,

where he stayed until the beginning of the Oxford Michaelmas Term - he wrote

"I think I should love Paris

[40] Terrell

367: "Perhaps the polite salesman is the same one celebrated by T.S. Eliot

in "Gerontion" as Mr. Silvero. Pound said that all the troubadours

who knew music or letters had been taught at 'the abbeys of Limoges Limoges " in both Gerontion

and Pound's Canto LXXIV, I can find no indication that Pound and Eliot were in Limoges

[41] Hugh

Kenner. As noted above, Hugh Kenner, following Pound, visited Excideuil in

1970.

[42] The

details that follow about the Poujol family and the former hotels in the rue

Gambetta in Excideuil come from the archives of the towns of Excideuil and

Montignac, from Filae.com, from Le

Maitron, and from conversations with Mme Jacqueline Desthomas-Denivelle who

was born in, and during her childhood lived in, the building that had formerly

been the Hôtel Mordier. By the time of the second world war it had become the

residence and surgery of Excideuil's dentist, Mme Desthomas-Denivelle's father.

[43]Roger

Hippolyte Poujol left Excideuil in 1912 and became a teacher, based around Le Havre and Rouen Germany in 1943, and died at Buchenwald

on 26 June 1944. (Le Maitron)

[44] The

Metropole mentioned in The Waste Land is

generally taken by commentators to refer to the hotel of that name in Brighton , and Mr Eugenides's suggestion of a weekend

there as an invitation to a homosexual tryst. Ricks and McCue (Eliot 2015, 659)

also notes that in "St Louis

[45] Source:

www.cparama.com/forum/cartes2012e/1349381079-24-Excideuil.jpg

[46] Source: EESP

[47] André Maurois (1885-1967)

was an académicien, historian,

novelist, essayist, and biographer. In France Britain

and of the United States Cambridge

Of

course I must admit that I am a little disappointed that Maurois should have

been the successful candidate, as he seems to me distinctly light-weight. But I

dare say he is a very good lecturer! (LTSE3, 449)

[48] The inscription on the

statue, removed from Algiers in 1962 and re-erected in Excideuil in 1969, reads

Thomas-Robert Bugeaud de la Piconnerie,

Duc d'Isly, Maréchal de France, Député de la Dordogne, Laboureur à La Durantie.

Maréchal Bugeaud (1784-1849) was prominently

involved in the nineteenth-century French conquest of Algeria and was, from

1840 to 1846, the first French Governor-General of Algeria, during which time

he won his famous victory at the Battle of Isly (1844) and the title Duc d'Isly. The Rue d'Isly in Algiers Algeria

[49] Source: EESP

Comments

Post a Comment